Ontario school board purchased U.S. “racial literacy” therapy program for educators

The York Region District School Board purchased “racial literacy” training by American clinical psychologist Dr. Howard Stevenson, whose work blends therapy techniques and anti-racism education.

The York Region District School Board purchased “racial literacy” training by American clinical psychologist Dr. Howard Stevenson, whose work blends therapy techniques, anti-racism education, and political activism in the American social context.

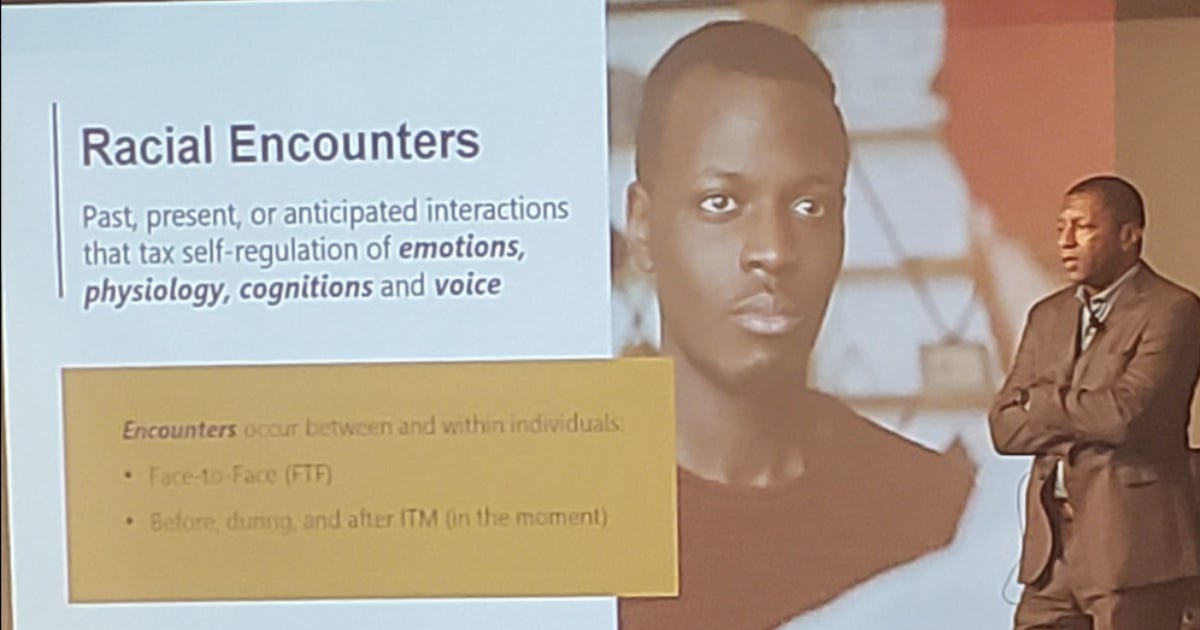

Stevenson’s method trains educators on “racial socialization-based culturally responsive therapeutic interventions.” In the United States, he is described as a leading figure in coaching families on how to prepare their children for “racial conflict.”

Exclusive Freedom of Information documents show the York Region District School Board paid $15,000 for Stevenson’s training in 2023. It is unclear whether Stevenson received payment in American or Canadian dollars.

The board has not released the presentation materials, but Stevenson’s online materials state that his method teaches educators how to identify “culturally relevant behavioural stress management strategies” by rehearsing racial slur scenarios and adopting psychological techniques to resolve “racial conflict.” The sessions often include collective-identity messaging and scripted coaching for black youth.

While the methodology is now offered in Canadian schools, Stevenson is based at the University of Pennsylvania, and his research and examples are heavily rooted in the American context, including issues of police violence and “racial trauma” unique to the U.S. social and legal structure. The work was initially designed for clinical and therapeutic settings, raising concerns about its uncritical transfer to Canadian classrooms.

The “racial literacy” work borrows heavily from clinical psychology, but the research behind these interventions consistently shows that an individual’s perception of race-based threats rises when they’re taught to monitor their environment—even when the situation is ambiguous.

A clear demonstration of this comes from research on “threat priming,” which shows that activating a specific harm in someone’s mind heightens vigilance and increases the likelihood that neutral or mixed signals will be interpreted as hostile.

These patterns appear in research on status-based rejection sensitivity; young adults who are prepared to expect discrimination begin perceiving more of it, independent of actual behaviour. The paper found that priming students to anticipate identity-based rejection increased misinterpretation of ambiguous social interactions and elevated stress responses.

The same mechanism has been documented in education when racial stereotypes are made salient during academic tasks, African American participants show heightened physiological stress responses, such as increased blood pressure, even without any discriminatory act taking place.

None of this research evaluates Stevenson’s program directly, and no studies have tested these “racial literacy” interventions across school systems. But the underlying psychological mechanism—training children to focus on identity-based threats increases both vigilance and perceived frequency of that threat—is well-established across decades of peer-reviewed literature.

The York Region District School Board confirmed that the board hired Stephenson, adding that his training is part of their “ dismantling anti-Black racism strategy.” They added that the board “delivered a series of presentations to staff as well as families” with the goal of “naming, noticing and disrupting anti-Black racism when it occurs.”

So plant the fear, let it fester and undermine everything. Talk about CREATING problems…

Has anyone tried going to other countries to 'get a feel' for how they treat other races??

Inbred beliefs aren't that easy to alter.

Schools can teach people to read or write but not how to feel.

Schools are failing on the read write part.