Ontario classrooms strained as immigration outpaces school capacity

Alberta’s teacher strike exposes how schools are buckling under the weight of mass immigration and an overwhelming number of students who speak little or no English.

Alberta’s teacher strike exposes how schools are buckling under the weight of mass immigration and an overwhelming number of students who speak little or no English. Ontario, too, is facing the same pressure. Newcomer enrollment is surging far faster than staffing, language supports, or funding, leaving regular classroom teachers to absorb a growing wave of English-language learners with almost no systemic adaptation.

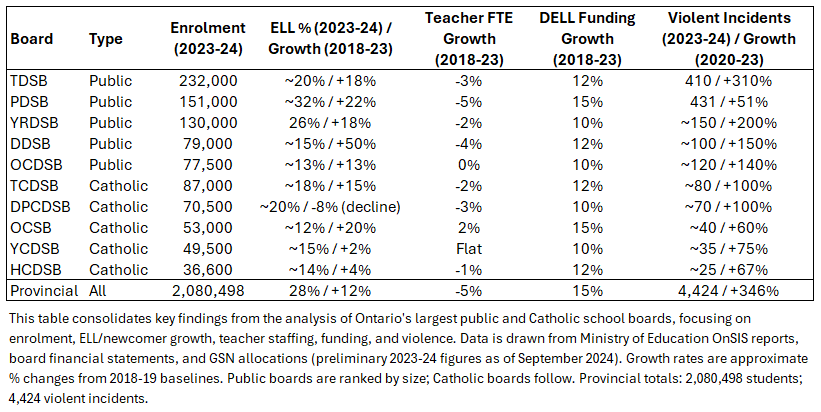

The number of English Language Learner (ELL) students—those who need extra support to succeed in English-language instruction—has risen sharply since 2018, reflecting broader federal immigration trends.

According to board and ministry data, the Durham District School Board saw the estimated numbers of ELLs rise by about 50 percent between 2018 and 2023, with roughly 15 percent of students now requiring support.

The Peel District School Board reported that multilingual students make up about 32 percent of its enrollment, and an analysis of the data found that ELLs increased by roughly 22 percent within the same period. For the Ottawa Carleton District School Board, the numbers rose by about 20 percent.

The Toronto District School Board reported that more than half its students speak a language other than English at home, and an analysis of the data found that ELLs increased by about 18 percent within the same period.

Government data show that while newcomer enrollment, especially in the Greater Toronto Area, is climbing sharply, the number of new teachers and language support has not kept pace.

In Toronto, total teaching positions fell 3 per cent over five years, while the number of English as a Second Language and English Literacy Development qualified teachers dropped nearly 9 per cent.

Peel’s teacher count increased slightly, but administrators report that many schools still rely on a single ESL teacher to support multiple grades and hundreds of students.

Funding for language support has also remained flat after inflation. The province allocated ELL funding increased by about 15 per cent between 2018 and 2024—roughly the rate of inflation, not enrollment.

The impact of these trends is visible in classrooms. Boards report overcrowded classes, cancelled programs, and increasing safety concerns. ELL students often arrive mid-year, requiring assessments and supports that schools are not equipped to provide quickly.

And teachers have been suffering the consequences. A 2024 report by the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario—Ontario’s largest teachers union—found that 77 per cent of educators had “personally experienced violence or witnessed violence against another staff member” the previous year. Four out of five respondents said there were more incidents now compared to when they started working.

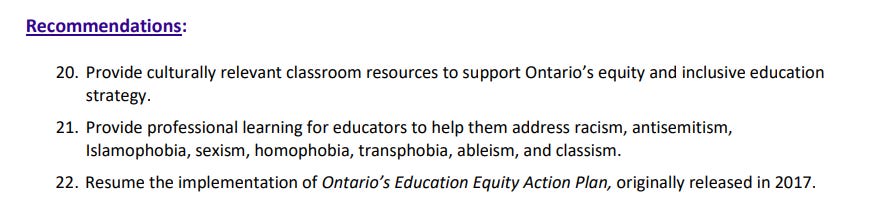

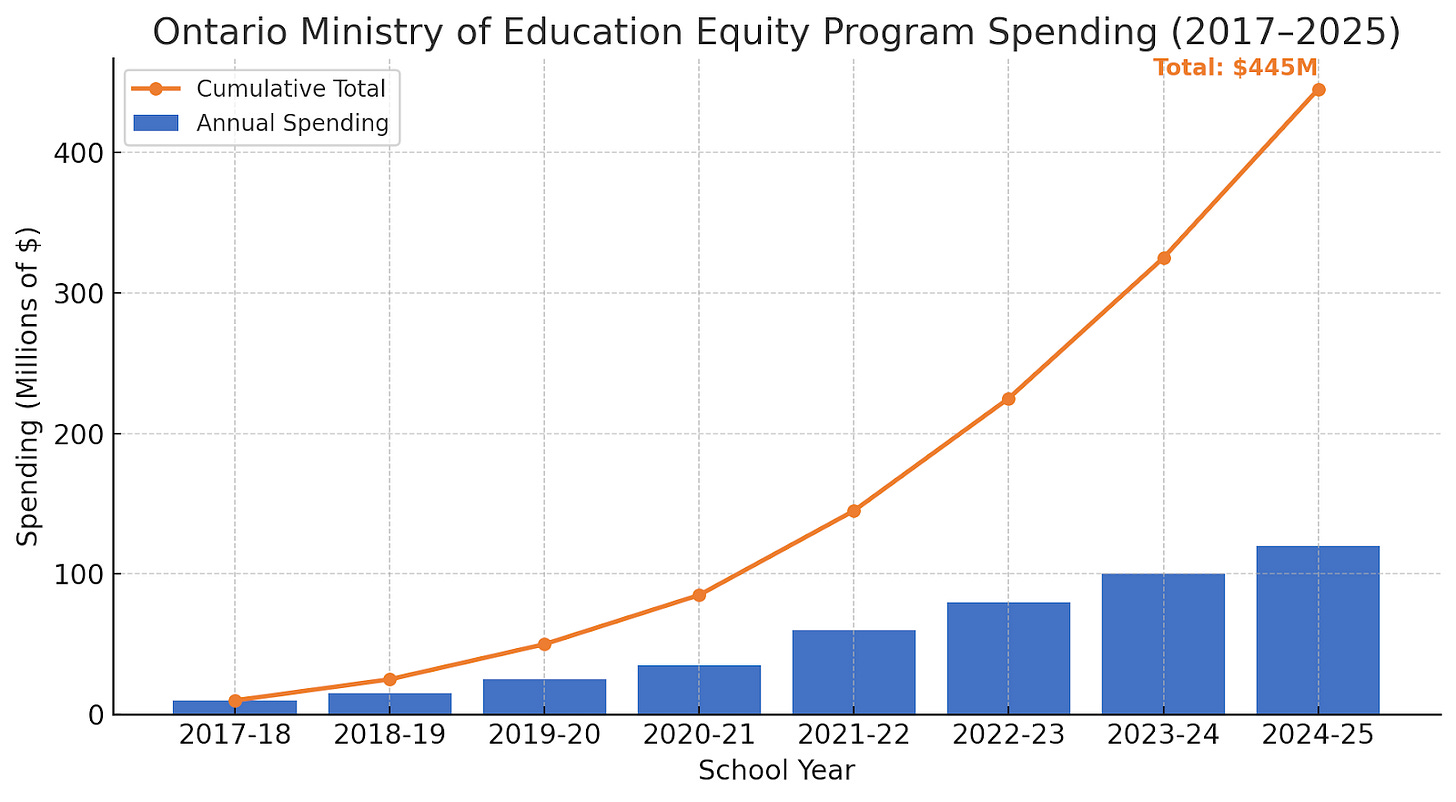

The union recognizes the additional pressures of “ large class sizes,” “inequitable access to in-school supports,” and the lack of “sufficient resources.” Their solution calls for additional ideological programming, even though provincial funding for such initiatives has already increased sharply each year since 2017.

A True North report found that projected spending on these programs is expected to exceed $500 million in 2025–26.

The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario described special education as being “in crisis,” while its 2025–26 funding submission emphasized early intervention and equity training. The Ontario English Catholic Teachers’ Association also warned of funding cuts and called for nutrition and anti-violence programs, without reference to rising newcomer enrollment.

Just a quick and most obvious question and one the likes of our Federal Liberals and OntArWeOwe's Doug Fraud still refuse to answer...

... That question ....

Is there anything in this country that has not been complete strained or worse destroyed by the farce that became our uncontrolled immigration which started with the election of that other farce with the fetish for weird socks..

You know... Katy Perry's now PET ROCK.